To read this story in Spanish, click here.

The percentage of adolescent Latinas attempting suicide in New York City has consistently been the highest compared to other racial groups for the last 20 years. While this has been a serious problem in the city’s Latino community, there could be a change thanks to three new bills that seek to end this tendency.

According to the Youth Risk Behavior Survey by the Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), 13.2 percent of teenage Latinas tried to take their own lives in comparison to 9.9 percent of African-Americans, 7.8 percent of Whites and 5.3 percent of Asians.

Suicide attempts by race in NYC

Carmen De La Rosa, a Dominican-American state assemblywoman who represents Upper Manhattan, is the sponsor these three bills that seek to make mental health services more accessible to young Latinas.

As someone who was raised between two cultures, De la Rosa knows that many Latinas often face difficult situations that can lead to depression, anxiety and other mental health issues if left untreated. When they don't have access to the help they need, many cases see suicide as the only solution.

“We know that one life is a lot to lose,” De La Rosa. “When an adolescent commits suicide, it not only affects the person, but it also affects the family, the school, it affects an entire community….we have to overcome this epidemic for our community, that in my opinion, is completely avoidable.”

On April 12, 2017, De La Rosa and the president of the Puerto Rican/Hispanic Task Force assembly member Marcos A. Crespo, introduced an amendment to the Mental Hygiene Law. If the bill passes, it will establish a Latina Adolescent Suicide Prevention Advisory Council. The 17-member committee would facilitate the coordination of resources and services; monitor the implementation of all the action plans; and submit an annual report to the governor with any political, legislative or financial recommendations to implement future action plans.

That same day, De la Rosa also introduced an amendment to the education and public health laws in New York State that would mandate that all medical professionals to receive cultural awareness and competence training as a requirement for their license to practice. This will assure that the doctors and medical professionals are aware of the linguistic and cultural factors that could affect a client when offering services to minority groups. In the case of Latino patients, this means that the professionals have to be able to understand the regional differences in Spanish.

Suicide has become the second leading cause of death among adolescent Latinas in New York State after involuntary injuries.

- NYS Office of Mental Health

De La Rosa is also de co-sponsor of the “Minority Mental Health Act” bill that would create the Office of Minority Mental Health within the state’s Office of Mental Health to ” satisfy the needs of minority groups.” The bill was introduced by state senator Kevin S. Parker on January 20, 2017.

The factors

Suicide is now the second leading cause of death of adolescent Latinas in New York State after unintentional injury. Even though there are many factors that lead people to commit suicide and each case is different, there are specific factors that affect adolescent Latinas. Some of them are poverty, cultural clashes, lack of access to mental health services and a stigma that exists in Latino cultures about mental health.

“The CDC defines suicide attempt self-directed behaviors with the intention of death,” said Jennifer Humensky, an assistant professor of Clinical Health Policy and Management (in Psychiatry) at Columbia University.

According to Humensky, there is a big focus on family, respect for authority and traditional gender roles within Latino communities. “ Conflicts arise when these young Latinas are exposed to American culture at school. This creates a pressure to balance both cultures,” Humensky said. She and her research team have found that family instability and the mental health of the teenagers’ parents can also be risk factors.

However, President Donald Trump’s administration has become a factor itself. Dr. Rosa Gil, founder and CEO of Life is Precious–the only organization in New York City that is designed specifically to help teenage Latinas who have self-harmed or attempted suicide–said the Trump’s anti-immigrant rhetoric has been affecting the adolescents participating in her program.

“This problem is not going away. It’s going to get worse,” Gil said. “Trump’s administration is threatening many in our community saying he will deport them. We have girls who come to the center crying thinking that when they get home, their parents won’t be there because there could be deported.”

Michelle Bialeck, the director of the Life is Precious center in the Bronx, also has seen fear among the girls who go to the center.

“All of our girls have immigrant families and many have undocumented family members,” Bialeck said. “Coming from an undocumented family causes a lot of anxiety and stress in these girls and a lot of times they feel like a big part of this country does not want them here.”

Life is Precious

It is a Thursday afternoon in one busy neighborhood in the South Bronx. The rain has stopped, the clouds have cleared and kids start filling the streets as the school day ends. A group of 30 teenage Latinas between the ages of 12 and 17 already have a routine. Instead of going home, they all go to the same place: Life is Precious.

Juliana*, 16, is one of the participants at Life is Precious. Sitting next to the window in the music room, she becomes frustrated trying to close it. She says she hates New York City. She feels suffocated by the urban chaos and sheer amount of people.

Juliana’s and other participant’s names have been changed at Bialeck’s request because they are minors.

Juliana was born in California to Vietnamese parents. When she was four years old, she was taken away from her mother who could no longer care for her. With few details about her childhood, Juliana said that she was adopted by a Puerto Rican family in the Bronx. She considers herself Latina, something notable in her Nuyorican accent.

She gets along with her adoptive father but not so much with her adoptive mother. She says that her mother restricts her and “ does not let [her] leave the house.” Family instability, financial hardships and general struggles of growing up led Juliana to self-harm. Because of HIPAA, Bialeck could not give any more details about Juliana’s situation.

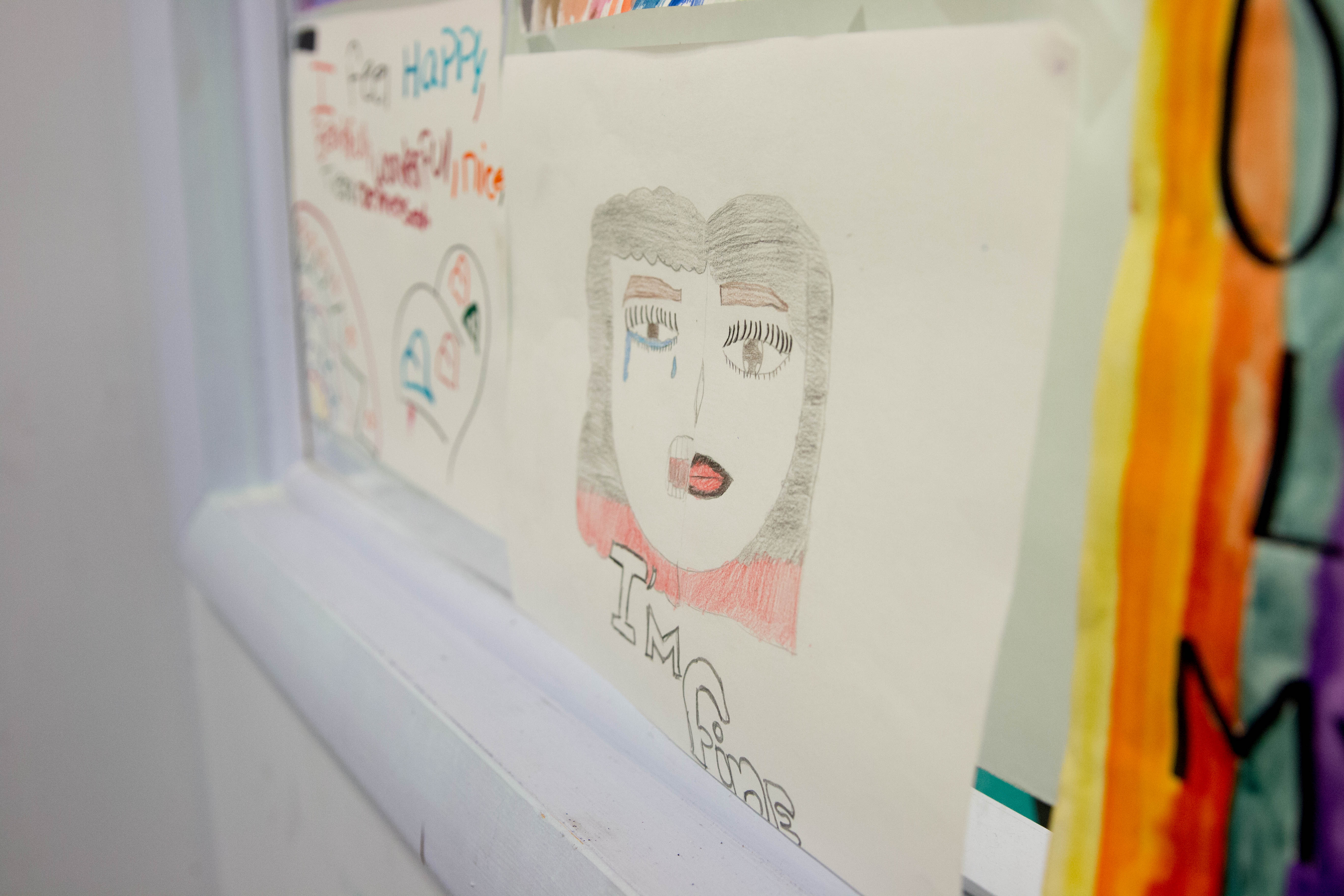

Juliana and her peers are lucky to have a safe space like LIP in the Bronx. They have access to art, photography, music and cooking classes. The center has rooms with colorful walls in which tutors helps the girls to do their homework and fill out college applications. These girls are also enrolled in therapy, something LIP requires the girls to receive in order to be part of the program.

“I feel free,” Elena*, 14, another participant of Puerto Rican descent, said. “It shows me how to cooperate with people.”

LIP was founded in 2008 in the Bronx. Of the 270 girls who have participated in the program, not one has made a successful suicide attempt, according to the New York State Psychiatric Institute/Columbia University.

However, the organization only has centers in three boroughs: the Bronx, Brooklyn and Queens. Gil has been planning to expand the program to Manhattan.

“What we know is that we have less Latinos living in Midtown and Lower Manhattan in comparison to upper Manhattan,” Gil said. “We are assuming that the place that needs the most help is Upper Manhattan.”

She said asked the city council for money in 2016, but the request was denied. A new center would cost at least $300,000. However, state senator Marisol Alcantara is willing to collaborate in this new project, according to Gil. Alcantara did not respond to multiple requests for an interview.

Other Initiatives

In Washington Heights, the Northern Manhattan Improvement Corporation (NMIC) helps people in upper Manhattan who suffer depression and anxiety. While many Latinos access this service, the organization does not offer services designed specifically to treat adolescent Latinas.

Morgan Siegel, who coordinates all the mental health efforts at NMIC, said that it is very concerning there are no centers in Manhattan that can help these young Latinas who have attempted suicide. “Having more resources for this community is the best way to deal with these issues,” she said.

In March, Connection to Care, an initiative supported by the Mayor’s Office that funds mental health treatments, awarded a five-year $1.2 million grant to NMIC and the bilingual, Bilingual Latina/o Mental Health Concentration at Teachers College at Columbia University.

The concentration, which was founded in 2014 in the clinical psychology and counseling department, is trying to close the communication gap that exists between the mental health professionals and Latino clients who seek treatment. According to itswebsite, this is the only program in the tri-state area that “offers adequate cultural training to offer mental health care in spanish Latinos.”

The students complete their fieldwork in different Latino communities in New York City. Some of them work with NMIC to help Latinos in Upper Manhattan.

“It’s important to understand the culture and the values of this community so we can incorporate in our interventions and treatment,” said Dr. Elizabeth Fraga, director of the bilingual program. “There are studies that show that 50 percent of minorities tend to drop out of therapy after the first session and many times is because we are not giving them the cultural treatment necessary to help them.”

Fraga said putting this program together was her dream. When she was studying psychology, she learned everything in English and then had to learn how to give adequate treatment to her Latino clients on the job.

“There are so many Latin American countries so you can’t just say ‘oh you speak Spanish, you can treat anybody,’ because the sayings are very different, the words are very different, the sociopolitical climate in every place is different,” Fraga said. “I really wanted students to have all this information before they saw clients.”

***

Now in LIP, Juliana has friends with whom she can share her experiences. She is enrolled in therapy that helps her deal with her anger. She loves that she is in a place where everyone speaks, or at least understands, Spanish. Bialeck and other staff members motivate Juliana to go to college to study forensic science and criminal justice. At 16, Juliana already knows that once she graduates from high school, she wants to leave New York.

At some point, her mom tried to convince her to enlist in the army so Juliana could get her tuition paid, but she told her no.

“I prefer the south like Virginia, North Carolina, South Carolina, Georgia, Texas,” she said. “I think life would be a little better there. Maybe not during childhood but after high school, because it’s just not as much there as it is here.”

Meanwhile, De la Rosa is continuously working to make sure her bills are passed and signed so young women like Juliana can get the help they need.

“One the main goals of this initiative is to educate our community to speak about the issue of suicide, that it is not a taboo, to talk about mental health and there is help,” De La Rosa said. “My goal is to educate and offer the necessary help so our youth can have a better and happier life. Youth should be a happy stage of your life and kids should have the tools available in case they need help.”