The Shadow Banks of the Barrio

For many Latino immigrants in New York City, an informal network of unregulated loan operators serve as the lenders of last resort. But borrowers soon find themselves buried in seemingly endless debt and haunted by intimidation tactics.

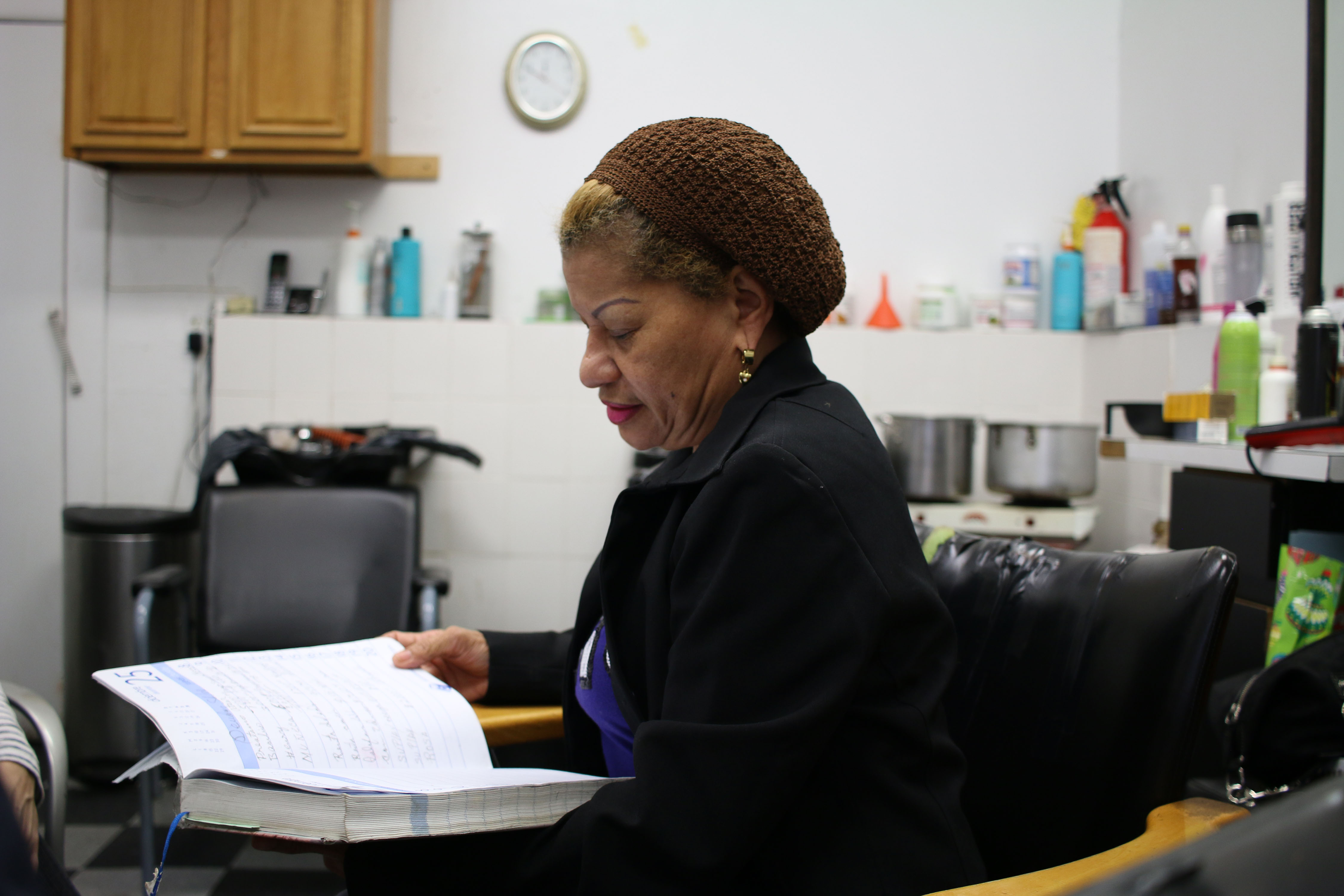

Maria Ramos holds a large, faded ledger propped open on her lap. The ledger was a gift from a beauty products supplier, an oversized agenda for 2014. Over time, it has become a repository of balance sheets—a record of the debts she’s accrued with neighborhood lenders known as prestamistas. At the moment, she’s paying interest on three loans totaling $14,000. She makes weekly payments, but the debt never seems to drop.

Ramos, 64, owns a beauty salon in Manhattan’s Washington Heights. In order to open her business, she borrowed money from three lenders who charge her 3 percent each week.

“I can’t sleep sometimes,” she says, sitting in one of the worn chairs where she cuts her clients’ hair. “I spend the night thinking about the debt."

Prestamistas serve as underground banks of last resort for many Latino immigrants. In New York City, which has the country’s second-largest Latino population, these unregulated moneylenders are familiar characters in several neighborhoods. Such informal financial services operate in a gray zone that caters to those with no access to credit from traditional sources.

But, like the payday loan operations that they resemble, prestamistas charge sky-high interest rates and can swiftly bury borrowers in debt. They also remain cut off from the U.S. financial system, hindering their economic progress and trapping them in a vicious cycle.

It’s hard to find hard numbers on the amount of money changing hands in the shadows. But evidence suggests the figure is in the tens of millions in New York alone: The Neighborhood Trust Financial Partners, which trains people from low-income backgrounds to participate in the U.S. financial system, has reports of cases where a single individual obtained up to $900,000 in informal loans. A 1996 survey by the Washington Heights and Inwood Development Corporation (WHIDC), found that informal lenders handled about $10 million in loans in just 10 blocks in Washington Heights.

Immigrants in U.S. cities have long relied on lending circles that allow members to pool funds and provide small loans to each other; such methods have helped generations of newcomers establish themselves.

According to a U.S. Financial Diaries research study of more than 200 low-income households, loans from family and friends are the second-most common credit choice in the United States.

Traditional banking institutions present particularly large barriers to newcomers, who might lack the credit history and other documentations needed to obtain loans. In 2015, some 45 million people had no credit history, and a study by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau shows that Hispanics are more likely than African Americans, Asians, or whites to be “credit invisible.”

45 million people

in the U.S. don't

have a credit score.

Among new immigrants who aspire to own a business and need funds, prestamistas are considered essential financing tools, says WHIDC director Dennis Reeder. His three-decade-old group offers an alternative: microloans to small entrepreneurs in the community, most of them Latino, with low annual interest rates.

The WHIDC also tries to make Washington Heights residents more aware of the risks of using these moneylenders. But for many, the benefits simply outweigh those risks. “It would be impossible for them to survive without lenders,” he says, “which is why they use them.”

Maria Ramos knew all about prestamistas when she borrowed money to open her business three years ago. The Dominican-born business-owner has been in the U.S. for more than 30 years, and during that time she’s borrowed from seven lenders, all either Dominican or Cuban, getting loans ranging from $2,000 to $35,000. Friends referred her.

She used to work inside her apartment, until she rented this small space in Washington Heights. There are no frills in her salon: Its furnishings include a wooden bench, a couple of office chairs, and five hair dryers, the old-school kind that look like space helmets. In a corner, two pots and an electric burner heat the water she uses to wash her clients’ hair.

She flips through the pages of her ledger, running her finger down the long list of names and amounts. She had to go to three prestamistas to assemble the $14,000 she needed to open her salon. Next to the names of each one she had scribbled the original debt and how much she had paid so far. Pressed on the final amount, Ramos hesitates. She’s unsure of the current balance.

Then, lowering her voice so her clients in the salon can’t hear, she quietly points to an entry from mid-April: “This is it.”

Ramos had only paid a third of the debt by paying $2,600 every month throughout 2016. By this April, she still owed $10,800.

Depending on credit history and outstanding debt, if she’d obtained a loan for the same amount from a conventional bank, Ramos would likely have paid about $350 a month for the same loan.

Prestamistas don’t loan to just anyone who seeks them out: Trust is one of the pillars of the neighborhood banking code.

Over one year, Ramos paid 208 percent interest on two of her informal bankers, and 156 percent on a third. “I tried to reach an arrangement with the lenders,” she says.

They now charge her an interest rate of 3 percent per week, cutting back on the principal to lower the monthly fee. In this scenario, it will take her even longer to get out of debt.

Last year, Ramos applied for a bank loan, but was rejected, she says, because she did not have a credit history. “I asked for a $10,000 loan, but what I got was a credit card for $7,000,” she said. “I spent it all on the salon ... and I didn’t keep up with the credit card payments.”

She doesn’t make that mistake with the prestamistas; she’s more committed to paying their weekly fee. When it’s time to collect, the lenders “stand there,” she says, pointing to the entrance of her beauty salon. “They come to get your money, and if you don’t have it, they start to make a show.”

Unregulated money lenders have traditionally been associated with loan sharks and the violence that comes with organized crime. But the prestamistas of New York City also tend to be neighbors, family members, and friends of friends; their collection tactics vary.

Ivelisse García, 48, works as a nanny in Manhattan; she got into the money-lending business three years ago, when she used her tax refund to make loans to family and friends.

On Saturdays, she turns her car radio to the reggaeton or bachata music from her native Dominican Republic and makes her rounds, visiting her clients to collect payments. She is often forced to return several times. “Sometimes I have to prepare myself emotionally before knocking on the door,” she says.

(Constanza Gallardo)

The customers of Doña Bella, as she is known, are close friends like Jorge, her hairdresser, and other people in her inner circle. “This business gives me the ability to do things for other people,” she says.

Her customers seek her out because they need cash to pay the rent, or for an immigration lawyer, travel and other expenses. She charges a weekly minimum interest rate of 20 percent. By law, interest rates for lenders in New York State are capped at 16 percent per month—one of many reasons why prestamistas operate in secrecy.

They also don’t loan to just anyone who seeks them out: Trust is one of the pillars of the neighborhood banking code. Customers are chosen because they are well known to the lender or are recommended by people who have the lender’s trust.

16% or more of interest

rate on a loan is

illegal in NY state

Loan approval in this system depends on the customer’s ability to pay on time, and also on the quality of recommendations to other prospective clients. Two of Ramos’s lenders cut her off after some acquaintances she had vouched for failed to pay back their loans.

“Everything is based on trust and a handshake,” says the WHIDC’s Reeder of the prestamistas. That’s part of the appeal of these lenders for immigrants who have trouble navigating the legal credit market, or have other reasons to avoid using traditional financial networks. “Many of them come from countries where their money is safer under the mattress than in a bank.”

A tour of 116th Street in East Harlem on a Saturday in pursuit of prestamistas confirms how important trust is: When asked where a lender might be, a street vendor replies with dismissive laugh.

“I know there are some, but I don’t know where they are,” he says. “They are not going to lend you money because they don’t know you.”

“I think it's worth going

with a prestamista. I think

they have lower interests

rates than banks”,

says María Mendoza.

Not all who seek the services of a prestamista are completely cut off from traditional banks. Take the case of María Mendoza, 56, of the Bronx. She has a traditional savings account but has never applied for a bank loan. Instead, she has been a customer of several neighborhood lenders for over 15 years. She deposits the money from these loans—$5,000 so far—in her savings account.

Listen to Doña Bella's story, a moneylender in the Bronx.

“My mom is in Puerto Rico, and I save money for an emergency,” says Mendoza, whose daughter, a bank employee, manages her account. She’s convinced that this arrangement makes sense. “Yes, it is worth going to the lender,” Mendoza says. “I think that they have lower interest rates than the bank.”

This isn’t the case, clearly, but prestamistas often take advantage of their their customers’ limited financial literacy. “The interest rates on informal loans are out of control,” says Eric Espinoza of the Neighborhood Trust Financial Partners, a participant in the city’s Financial Empowerment Center program, which provides monetary education and counseling. “There are cases of customers who pay 300 percent interest.”The way out of the informal banking cycle, advocates say, is to gain more knowledge about the U.S. banking system and to build a proper credit history. Espinoza says that it’s important to create strategies to convey information via word of mouth about people who have managed to get out of debt to lenders. This mechanism would take advantage of community channels and create confidence.

(foto: Monica Cordero y Constanza Gallardo)

But the need for fast money and persistent problems meeting bank requirements keep feeding business back to the prestamistas. For all their drawbacks, the neighborhood lenders are part of the community’s culture. Despite her debt, Ramos says she can’t complain about them, because they have “saved her life.”

She asked WHIDC for a loan, which is still pending to be approved, to pay off debts to her three lenders and her credit card. But now she has other plans: She will invest that money in a new beauty salon instead.

“If I can put the business where I am thinking about putting it, I will work more,” she said. “Maybe I will win new customers.”

This story was published in CityLab.